Opinion – The Electoral College: A Fundamental Flaw of American Democracy

The U.S. Presidency is arguably one of the most powerful positions one can hold on both the national and global scale. As head of state to a country of over 330 million, overseer of an economy with a GDP of $23 trillion, and commander-in-chief of the world’s third largest military, the President of the United States holds immense political, economic, and military power.

In addition, the power of the president has only grown since George Washington was sworn in as the nation’s first commander-in-chief over two-hundred years ago. Initially the leader of thirteen loosely-amalgamated states, the presidency has grown to a director today of a bureaucracy of over 2 million.

Considering the enormous power and influence of the U.S. presidency on both the national and global level, it doesn’t seem far-fetched to say that the American populace should have a say, or at least equal representation, in the election of the president; however, the U.S. president is chosen through the Electoral College, a system of elite democracy that, according to a recent poll by the Pew Research Center, only 35% of Americans support maintaining.

So, what is the Electoral College, and why is it flawed?

What is the Electoral College?

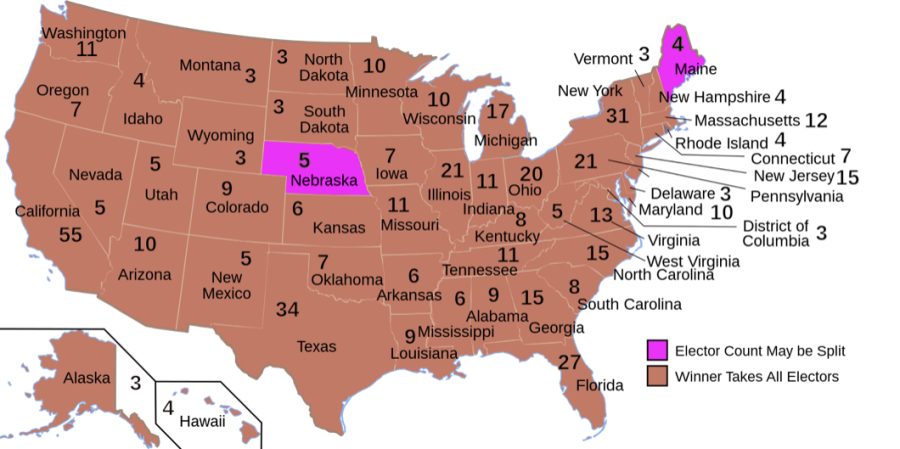

The Electoral College was established with the adoption of the Constitution in 1789 and is described in Article II, Section 1 of the document: “Each state shall appoint… a Number of Electors, equal to the whole Number of Senators and Representatives to which the State may be entitled in the Congress.” In this system, each state has a certain number of electors that vote for the president, equal to the total number of U.S. senators and representatives from that state. For example, Massachusetts has 9 members of the U.S. House of Representatives in addition to its 2 senators, giving it 11 electoral votes.

The process for determining electors varies from state to state; in Massachusetts, along with six other states and the District of Columbia, electors are chosen by central committees for each party with a presidential ticket. In December, following the presidential election in November, the electors whose candidates for president and vice president won the plurality of state votes meet to cast their own votes for president and vice president. To win the Electoral College requires at least 270 of 538 electoral votes.

Issues with our Electoral System

Though the Electoral College is flawed in multiple ways, its overarching issue is the system’s failure to give American people true input in determining the U.S. President. When casting a presidential ballot, citizens are not adding to a tally that will directly determine their leader but will merely influence the voting behavior of electors, their unelected representatives.

It could be argued that a true participatory democracy where everyone’s vote counts may not be needed to fairly represent Americans’ political ideologies; in fact, many of America’s political institutions are based on principles of republicanism, where citizens’ views are represented by elected officials, such as in the U.S. Congress. In elections for president, though, electors in the Electoral College are not directly voted on by their constituents in the way that senators or representatives are.

In addition, in all but two states (Maine and Nebraska) where electoral votes can be split between districts, electors from a state will all vote for the candidate with a plurality of votes (though “faithless” electors in some states will sometimes vote differently). While this does allow for a state’s voting plurality to be represented, the “winner-take-all” system in place in most of the country effectively extinguishes minority opinion, especially in party stronghold states.

For example, California, a strongly Democrat state, gave all its 55 electoral votes to Joe Biden in the 2020 presidential election. Over 34% of California’s voters voted for Donald Trump this same year, though, but none of the over 6 million Republican voters were represented in the state’s electoral vote.

The “winner-take-all” system of the Electoral College also creates “swing states”, states that have particular importance in presidential elections and change the party they support regularly. A party stronghold like California will predictably lend its electoral votes to Democrats in elections, but states like Pennsylvania where party power is more evenly split can have much greater influence in determining the outcomes of presidential elections. In the 2020 presidential election in Pennsylvania, a state that Donald Trump had narrowly won in 2016, Joe Biden only won the state’s popular vote by 1.17%, but gained all 20 electoral votes through the Electoral College.

The “swing state” phenomenon can also lead to presidential candidates spending disproportionate amounts of time and money campaigning in these states; according to NPR, nearly 90% of campaign funds for television leading up to the 2020 election were spent on just 6 battleground states-Pennsylvania, North Carolina, Florida, Arizona, Michigan, and Wisconsin.

In addition to the issues caused by the “winner-take-all” system of the Electoral College, the process used to determine the number of electoral votes a state has creates a power imbalance between them. Since the number of electors a state has is determined by its number of U.S. senators and representatives, states with smaller populations and less representatives have a relatively greater share of electoral power than larger states. Wyoming, a state with 1 at-large representative and 3 electoral votes has about one vote for about every 180,000 people, whereas California, which has 55 electoral votes, has each electoral vote representing over 700,000 citizens. This gives greater power to voters in states with smaller populations like Wyoming and Vermont, as well as the candidates they support.

Changes for Democracy

In the era of its creation, the Electoral College may have seemed a reasonable system to the founding fathers; citizens’ access to national political information was much less in the late 18th century than it is today, which might have made an elite democracy more justifiable. Alexander Hamilton, one of the framers of the Constitution, wrote in Federalist no. 10 of the dangers of majority “factions” and mob rule, a fear that could certainly make one hesitant of granting direct voting power to millions.

In the age of the internet, though, Americans are exposed to more political thought than ever, and nearly everyone has some stance on our nationwide elections. Presidential candidates are seen everywhere from phone screens to television, their platforms being broadcast daily to hundreds of millions. Considering America’s informed voter base today, direct participatory democracy seems much more reasonable.

One widely-proposed solution is a switch to a popular vote in presidential elections. According to the Pew Research Center, about 63% of Americans are in favor of this switch, and 65 out of the world’s 125 democracies utilize this method in determining their head of state. In 1969, the House even passed a proposed bill that would replace the Electoral College with a popular vote, though the bill never passed the Senate.

Another potential way of amending our electoral system would be to split states’ electoral votes based on geographic lines. Two states-Maine and Nebraska-already split their electoral votes, allowing for a state to cast its votes for more than one candidate. Using a system of electoral districts could help account for the geographic political divide that exists in many states (rural areas generally lean Republican, urban areas generally lean Democrat), and give representation to minority voters. With geographic districts, though, comes the potential for gerrymandering, where a political party in power draws districts in a way that advantages them in elections.

When a group of 12th-graders from Oakmont Regional High School were asked about their opinions on our current electoral system, responses were mixed. One student who was in favor of abolishing or amending the Electoral College cited the phenomenon of “swing states”, saying, “It makes zero sense to have our presidency decided by only a couple of states.” Another student expressed a more sympathetic view of our electoral process; when asked the same question, he responded, “On paper, it may seem like it is doing more harm than good (but maybe it’s not). As with other parts of government, though, there are aspects that the common man doesn’t understand. I’m sure there is a really good reason to not have a true democracy. Good presidents have been elected with the [Electoral College].” Multiple students, though, described their lack of familiarity with the process, and held no strong opinions on the issue.

To abolish the Electoral College would truly be an immense task, as amending the Constitution usually requires a two-thirds vote in the House and Senate in addition to ratification by three-fourths of state legislatures. Considering the unfairness of the system, though, and its failure to accurately represent Americans’ diverse political views, it’s safe to say that it’s time for a change. As the Founding Fathers stated in the Declaration of Independence, “Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, –That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it”; does the Electoral College truly live up to these ideals?

Henry Telicki is part of the Class of 2023 at Oakmont. This is his third year writing for The Oakmonitor. Henry is a member of the cross-country team at...