Re-enacting is a sweaty, driven, and heartfelt sport for the soul, and for some, it may have a positive impact on mental health, potentially contributing to a shift in well-being. For me and many others, it’s been nothing but a positive experience, that fosters long-lasting relationships and essential learning experiences in each and every member.

Typically a Re-enactment doesn’t start until the morning of the second day. The camp is set up the night prior and everyone usually spends their time in “civilian” clothing (the clothes they wore when they arrived at the event) until bed. Depending on the ground you’re camping on, re-enacting can either benefit your sleep or cause excruciating back problems; Which is why most tents inhabited by a reenactor with 15 or more under his or her belt have cots to sleep on. But as for the younger fellows who want to inherit back problems shortly, we sleep on the ground. Typically, inside of a frame tent, which is made of one canvas tarp and 3 pieces of wood that provides “exceptional” protection from the elements and keeps the body inside warm!

Inside, the setup is as follows. Modern tarp for protection against the wet ground. The floor tarp is just another piece of canvas that acts as a floor for the tent. Then usually a blanket, sleeping bag, and another blanket. Above you are metal hangers for your uniform, and usually a lantern. Most of the other belongings are fitted to be stuffed inside a wooden supply crate that’s placed in the corners of the tent. Historically, these tents were only really used during the winter, as the soldiers in the Civil War were too busy dying or fighting to set up camp and would sleep on the bare ground if they got the chance. But when used, it would fit about 5 or 6 people inside the tent. As for re-enactors, we each bring our own tent and prefer to bunk alone.

The first rays of daylight barely make it through the tent’s canvas, but when the camp comes alive, it’s as if the entire 19th century has suddenly returned to life. You’ll hear it before you see it—shouting, boots on dirt, the clang of metal tins hanging off of haver sacks, A trumpet blast, or the little drummer boy marching back and forth in front of your tent. The low groan of horses getting their morning feed from the Calvary pairs well with a morning sigh, or yawn despite the long morning of drill ahead. The reenactors are up, and, more often than not, they’re grumbling about it. Nobody’s ever truly prepared for the abruptness of the morning routine, but that doesn’t stop it from coming.

In the words of my late father, ¨ There always some wood to be splittin boy.¨ Especially for the younger guys with the, ¨Unused backs¨, that ¨Never saw a day of work in their life.¨ But, something about waking up and contributing to a community first thing in the morning. Making sure that your family away from home has heat for their hands, and their food in the morning drives the axe down every time. But first, a re-enactor has to get dressed.

Once you throw your shirt and pants on (which sounds easy until you try to put on suspenders for the first time) You can put on your socks, shoes, and vest. Most re-enactors if not in leather boots or an old pair of leather sneakers, are wearing Brogans. A type of shoe from the eighteen hundreds that were easily mass-produced for the war effort at the time. These shoes feature a wooden sole, hard leather pieces formed to be the shape of a boot, nailed to the wooden soles and laced together with rope made of animal intestine! But it certainly grows on you after a while, I personally love them. Finally, a re-enactor wears a Kepi or hat (depending on the side) and has to remember it along with his canteen wherever he goes, for they are the two most important things. ¨Hydration and identification, prevent permanent isolation¨. I just made up that quote so don’t forget it. But once you’re dressed you can go ahead and head out into camp.

Right about now, the sergeant’s voice cuts through the mist like a dull axe. “Revelee!” he bellows again, no less grouchy than the rest of us, and in a tone somewhere between military discipline and a call to arms. This word essentially means, ¨You better be up and ready to go right now and movin, or Mr water Bucket is coming to take a morning nap in your tent.¨ By now, most of us have learned to treat it as the unavoidable good morning of another 12-hour day spent lugging gear, marching, and pretending to fight a battle that’s been over for more than a century.

But before the cannons roar and the flags are raised, there’s the business of breakfast. The kind of breakfast that’s eaten out of tin cups and with hands that haven’t yet had their first wash of the day. Canteens are filled, firepits stoked, and if you’re lucky, someone’s got bacon frying over an open flame, and the food is always as good as it smells in the fifteenth mass. Some guys might start sharpening their bayonets, others practice their drill moves, but everyone is a little too focused on surviving the next few hours to feel the weight of history just yet.

The camp is a strange mix of the old and new. You’ll catch glimpses of modern life creeping through the cracks. An occasional cell phone will beep from under a blanket, a plastic water bottle might roll out of a wooden crate, or someone’s trying to charge a camera with a car battery. Steve Wraph, our company chef and Santa Clause calls this ¨The breaking of the Disney magic.¨ But then, just as quickly, someone will slap on their woolen kepi and you’re swept back into 1863. The sight of soldiers lined up in period-correct uniforms, each meticulously patched and worn, guys that you were just laughing with now plastered with a stiff straight face and furrowed brows, somehow erases any thoughts of 21st-century convenience. For a moment, it feels real. Real enough to trick your mind into thinking you’re a part of something real and important.

As the day progresses, the camp morphs into a bustling mini-city—huddled around campfires and open-air kitchens, full of men who are more like family than anything else. You’ll hear stories of battles fought, of ancestors who walked the same paths, and sometimes, of someone’s great-great-grandfather who swore he fought at Gettysburg—though he wasn’t quite sure. After all, history in the making is never quite as clear as the textbooks make it out to be.

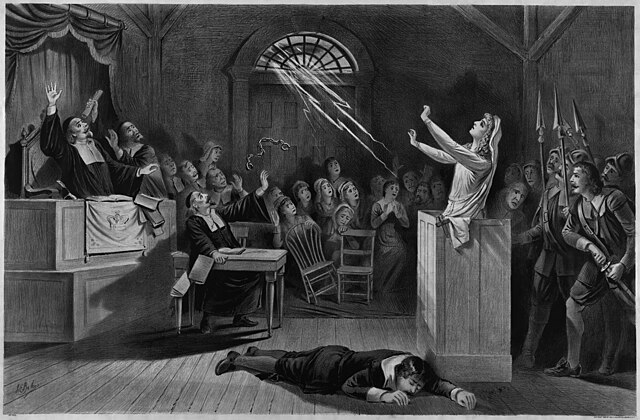

By mid-morning, the camp is primed for battle. Uniforms are tightened, muskets loaded, and the air is thick with men shouting orders, adjusting gear, and trying to get the perfect alignment for that “authentic” photo op. You’ll be told where to stand, what to say, and how to march—no one’s left to improvise too much. That’s where the beauty of the whole thing lies, though—there’s a structured chaos to reenacting, a kind of rigid free-for-all where nothing goes as expected, and yet everything still feels like it does. If you step out of line you can be sure the guy behind you will pull you back into formation, or quickly correct your marching.

Then, just as quickly as it began, the first canon fires. It shakes the ground beneath your feet, rumbles through your chest, and reminds you why you’re there: not for glory, not for fame, but for the experience of standing in the same place your ancestors did—at least in spirit. You can’t help but feel the connection to the past. Expert opinion, Tom Connell, Head of the Confederate State of America and former Captain of the 15th Massachusets says this about re-enacting, “I would say that, it’s given me the opportunity to spend quality time, both with my Father when he was around, and my children now, away from the distractions of modern time, and technology. I think it’s enabled us to have our own “just us” space. Where there’s no technology and it’s just people and relationships. It’s something I think we’ve lost today, the purity of communication and friendship.”

Because when you’re out there, in the heat of battle (real or imagined), everything else falls away. The modern world fades, and all that’s left is the camp, the musket smoke, and the knowledge that, for a brief moment, you’re no longer just a reenactor—you’re a part of history, reliving it the only way you can: on the ground, under the canvas, in the fog of war. And when it’s over, and the guns fall silent, you’ll return to the real world, nursing sore feet and a sore back, but always with the memory of what it felt like to be somewhere else—somewhere a lot less modern.

“You can find a lot of enjoyment and satisfaction in human relationships, and we don’t. My only regret is that I didn’t do it years earlier when my father was still around.” -Tom Connell

natalee • Dec 18, 2024 at 3:43 pm

i love you brenton